7 May 2011

Fresh lick of paint

I received an email this morning from a mural artist with an interest in working to restore/repaint Ghostsigns in the UK. She found me via a great project being run by the London Mural Preservation Society. I started drafting a response and then realised I’ve never written specifically about this topic and thought a blog post would be a good way of bringing the various strands of thinking and work done in this area together.

The first thing to point out is that this type of activity is quite popular in the USA. This may be because Americans seem to place more value on their relatively recent history that we do in the UK. In fact, in his book, William Stage dedicates an entire chapter to this process of restoring signs. A recent example of this work in the USA can be seen on the Alpen Beer sign in St Louis (article here [Link expired] and finished product here).

There is also evidence of Ghostsigns restoration in the UK, although from the collection gathered for the archive there are only a small number that have had this treatment. One famous example is the Bile Beans sign in York which was repainted in 1986 by the York Arts Forum, with help from artist Baz Ward* (At the end of this post are some more photos of signs that have had a fresh lick of paint in recent years, including some before and after examples.)

In my article for The Ephemerist I briefly discussed the issue of repainting Ghostsigns and concluded that something is lost in doing so, despite the fact that when the signs were advertising contemporary products and organisations they would have had their paintwork regularly refreshed:

“Recreating the brilliance of the colours and the messages being conveyed offers some insight into how striking these advertisements would have been when they were fresh and young. However, something is lost in doing so. The position the signs hold within individual and collective memories relates in some way to the survival of the decaying original rather than any attempt to restore it. While the signs would have received fresh coats of paint when they served a genuine functional purpose, there is a superficiality reapplying the paint when the sign is devoid of this purpose.”

The debate around the rights and wrongs of restoring Ghostsigns should also consider the possibility of whether it would ever be possible to truly reproduce the colours and layouts of the original signwriters. Clearly this issue would also have held true while retouching them when they were serving as genuine advertisements.

It would be interesting to consider which groups and organisations might hold an interest in funding or directly carrying out this kind of activity. The Bile Beans example above was organised by an arts group, but other possible candidates might be local history societies, property owners and contemporary brand owners who once used this form of advertising. In the case of a local history society there is a question over whether repainting a sign would add or detract from the historical significance of the location? Bas Groes and I deal with this challenge briefly in our Literary London article when we considered the potential for protecting and preserving Ghostsigns:

“The act of preserving is problematic in itself: in his classic, anti-Thatcherite exploration of London’s cultural history Theatres of Memory (1994), Raphael Samuel is opposed to the artificial conservation of historical sites by the heritage culture that has sprung up since the disconnections taking place during the sixties, not because he finds that such sites in themselves are not worth preserving, but because their preservation implies the contrived, and motivated rewriting of a nation’s cultural and historic narrative for political and conservationist or ‘ressurectionist’ strategies are dangerous because they are based on delusional ideas about a nation’s past, reinforcing myths of loss and stereotypes that lead to cultural regression.”

Later in that article we warned against falling into a “trap of naive nostalgia”, citing as evidence a piece lamenting the loss of the town crier to advertising posted on walls:

“Amid all the changes which this changing age has produced, that of the walls superceding the town’s bell-man is perhaps the most melancholy. The loss of these functionaries has been a sad blow to corporation patronage in many of our good old towns. In looking back into the dreamy past with all its misty enjoyments, sonorous sound of John Hotton’s bell, and his stentorian voice, (which could be heard from a distance of about three miles, weather permitting) yet sounds in all its vibrating cadence upon our green memory.”

The Language of the Walls by One Who Thinks Aloud: pp.383-84

I would probably conclude that my own views on this debate are agnostic. I don’t have a strong belief that we must conserve all of our Ghostsigns, but neither do I think that doing so is wrong. If groups form and raise funds to carry out this kind of work then all power to them. However, I strongly doubt that a national movement of sufficient strength would ever form to go about the work of repainting them all. Besides, there are many which probably wouldn’t warrant such treatment even if I did think it was the right thing to do. These Ghostsigns vary in appearance from artwork to eyesore and those that have survived have done so without any protectionist measures in place.

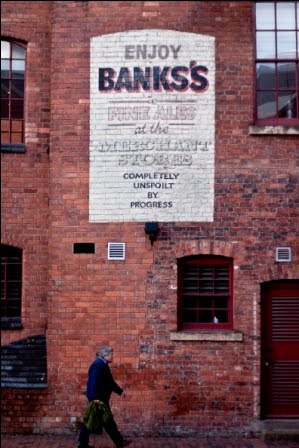

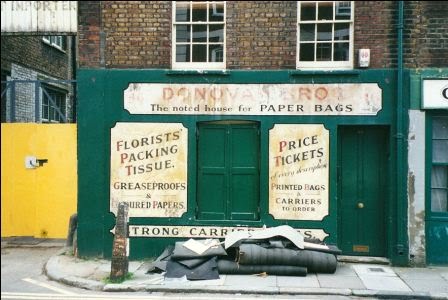

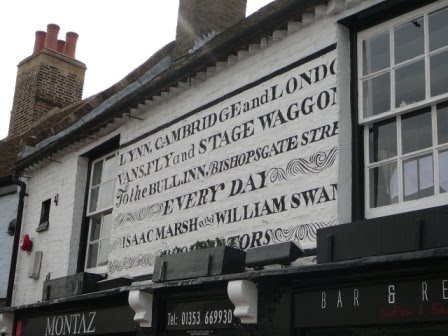

I think that what I would prefer to see is the resurrection of the craft of signwriting and the emergence of hand painted advertising on walls as a viable and effective means of advertising. With companies such as Colossal Media and Walldogs plying their trade in the USA it is perhaps only a matter of time before we see more fresh paint on this side of the Atlantic, not being used to bring back the past but, instead, to push the craft forwards in new and innovative directions. This is something that I would fully support and we have already seen Bob & Roberta Smith and Sussex County doing it on a small, local scale. Maintaining and developing the skills required to produce these signs would seem a far more valuable enterprise that painting over the work of craftsmen long gone. However, as we see in the examples below, when it has been done it gives a good representation of how much impact this form of advertising can have…

Please add any of your own thoughts or discoveries in the comments.

*Correction, June 2013: Baz used the sign as a subject for his own painting and was not involved in the restoration work of the York Arts Forum. Full details of this sign’s fascinating history can be found linked from this blog post.