1 Mar 2021

Whitewashing History at Poland Street Car Park

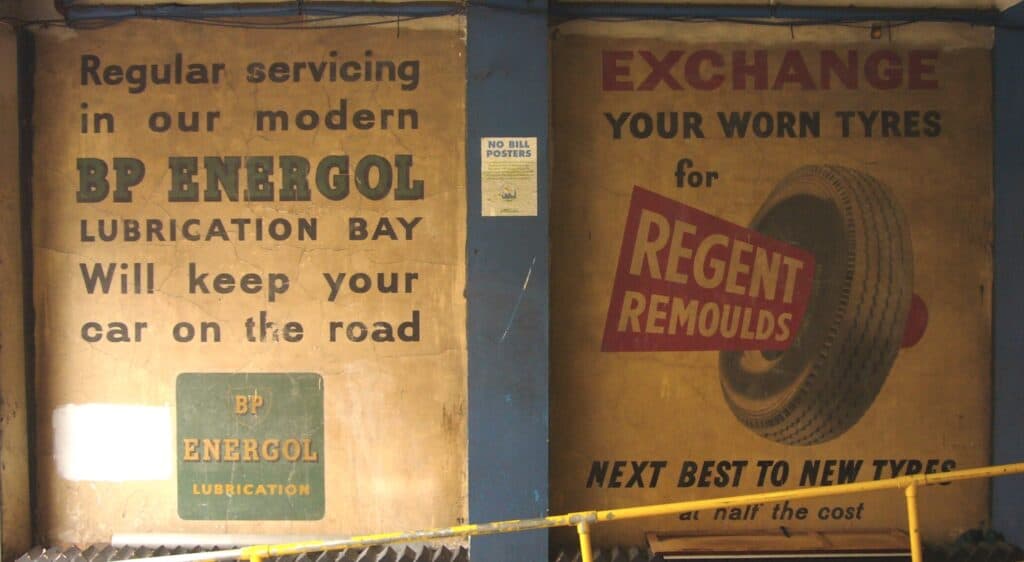

Last week the popular ‘double’ for BP Energol and Regent Remoulds at the entrance of the Poland Street car park was the latest Central London ghost sign to be lost. They were whitewashed over, presumably by the owners of the property, in order to cover the graffiti which had rapidly built up over the last couple of years. At the end of this post I’ve pasted some historical notes on the pair, but first a discussion of their long-term presence and sudden disappearance.

My guess is that for a long time these painted billboards were covered by mounted signs. Then, for a period, they were left exposed and in good condition due to this earlier protection and their sheltered nature. My photo above is from May 2008. Seven years later in 2015 the first piece of graffiti can be seen on the left of the BP sign. It took a little while, but this soon became an avalanche, resulting in a mish-mash of tags and larger pieces all overlapping. Adam Orton‘s photo shows the scene in June 2020.

The first issue here relates to the conflict between ghost signs and graffiti. There has often appeared to be a degree of respect towards ghost signs from the world of graffiti, but situations such as this one are not rare. Street art (if considered distinct from graffiti) is also guilty of encroaching on ghost signs e.g. Boyd Pianos.

At its heart this is a question of what has legitimacy on our streets—two pieces of 1950s advertising, or a medley of 21st Century ‘works.’ In theory they can co-exist in palimpsest, but the attitudes of property owners tend to be against graffiti, hence the whitewashing that we see here. (I’m assuming it’s the owner, but it could be the council, or mandated by the council.) It would be interesting to gain insights into public opinion on the matter, comparing the three key stages (advertising/graffiti/whitewash) and seeing how important personal taste is in these matters. The point is that ownership, while legally with the landlord, is shared with the wider community and public and so we are all ‘stakeholders.’

A related issue is if some form of protection, physical or legal, would have helped. Clearly Perspex coverings like those at Leytonstone Station and elsewhere would have offered a shield against graffiti. Given their street-level position this would likely have been far more effective than, for example, having the signs added to the Westminster Local List. The Local List would have made no difference to the owners’ right to paint the walls, as this is classified as redecoration, with no planning permission required.. The Lambeth Council response to the painting over of the Music Roll Exchange sign in 2007 sets this position out clearly.

Perhaps the biggest irony here is that the whitewashing is likely to result in what the owners could consider to be the worst of all worlds. They have now effectively prepared a lovely fresh canvas for the next round of graffiti, while also completely losing any sight of the history on the wall beneath. The Army Club/Westminster Gazette palimpsest at the start of my Stoke Newington Ghostsigns Walk offers an excellent example of such a counter-productive action.

In theory the signs could be brought back with the right treatment, but it looks like a position has been taken to engage in a long-term game of cat and mouse with the spray-can crowd. While this continues we can at least rest assured that somewhere beneath it all, these two signs are still there, waiting to be revealed again. When that happens we can once again look at them and tell their story as follows.

This pair of signs can be dated to the early 1950s when Energol began to be marketed as a BP (British Petroleum) brand and Regent Remoulds were using the tyre and pennant illustration shown. BP Energol engine oil was launched in the late 1940s as a partnership between Price’s and Anglo-Iranian and was touted as “the oiliest oil” even after the takeover by BP. Regent Remoulds were based in Edmonton, North London, and Manchester, and offered a low-cost alternative to new tyres in post-war austerity Britain.

The signs were painted as mini-billboards at the entrance to what is still a Central London car park. When it opened in 1925 it was the UK’s first multi-storey car park, with six floors capable of holding 500 cars. While this was a novelty at the time, today’s driver may have been more taken aback by the provision of various extras, including waiting rooms and facilities for chauffeurs, car washing bays and even dressing rooms for those parking and heading out on the town.

Thank you to John from Soho, and Adam Orton for the photos used above.