7 Jun 2021

Pinterest, Planning Permission, and a Prime Advertising Wall

Pinterest, via their outdoor media agency, got into a bit of a pickle recently when trying to install some new banners. The events once again raise interesting questions over planning, and permission, in the public realm.

Recent Events in Hackney

The first installation on Saturday was on Stoke Newington Church Street, which led to an immediate response on Twitter, largely due to the use of a wall which hosts a community mural. (Read this 2017 blog post for a more detailed history of the wall itself, up to the point of that mural being painted.) Next in line on Sunday morning was a wall on the Rio Cinema, a Grade II listed Art Deco building.

In the case of the Stoke Newington Church Street installation, no planning permission had been sought for advertising by the landlord, estate agency Next Move. This meant that almost as quickly as the sign went up, it had to come back down again and the mural is once again visible. I assume the same will happen to the Rio one, although the position isn’t clear at the time of writing.

Continued Use (or ‘Grandfather’ Rights)

One of the questions raised by the incident is whether there could have been any ‘inherited’ planning permission given the wall’s previous use for advertising. In America this is known as ‘grandfathering’ i.e. signs that wouldn’t pass today’s planning requirements can continue to be maintained in light of their historical presence.

An explicit case of this kind occured in 2007 when planning permission for a billboard was refused. The outdoor contractors, ClearChannel, appealed on the basis that there was a ghost sign on the wall and so the installation of a billboard was simply a continuation of this advertising use. The judge threw that argument out because the sign hadn’t been operational for many years. (Some more of this story will be told in the book in a wider discussion of protection and preservation issues.)

I suspect that any attempt to argue along similar lines for the Stoke Newington wall would face a similar fate. However, its use for the mural, also without planning permission, leaves a slight grey area. If, for example, the new advertisement had been painted along similar lines to the mural, then it could be argued that this is indeed a form of continued use. (Thanks to Nick Perry for his observations on the finer points of this type of planning argument.)

For now the mural has been saved from being covered by a new advertisement. However, it highlights the precarious nature of walls in the built environment, and no doubt there will be more cases of this kind in the future.

Ethics in Advertising

The other big question that this raises concerns the role of advertisers in managing their supply chains. Pinterest claims not to have known about these proposed sites, and would have delegated the role of booking them to their outdoor media buyer. They in turn solicited the walls from the landlords. The issue is to what extent Pinterest can be held responsible for these arms-length activities that violate planning regulations and are arguably not in the public interest.

(The use of sweatshops by major manufacturers comes to mind, where the argument presented is often that they are a number of steps removed and so can’t be held responsible. Multiple layers of subcontracting are commonplace in many industries, giving wriggle room to the ultimate paymasters.)

Campaigns such as Stop Funding Hate have brought the issues of brands and advertisers supporting particular media outlets to the fore. A growing list of companies have responded to consumer pressure and instructed their media agencies to withdraw their advertising from specific publications and media owners. In America there are similar movements against broadcasters such as Fox which are also gaining momentum.

This case leaves the question of Pinterest’s culpability open. It will be interesting to see if there is any direct response from them in terms of their dealings with the media buying agency responsible. And, in turn, if that company reconsiders its approach to soliciting walls in conservation areas, or from particular landlords.

Taking a step back from all of this detail, there is a broader question over the legitimacy of outdoor advertising itself. I regularly recommend this 1960 article by Howard Gossage which makes a very strong case against…

PS. A New Clue

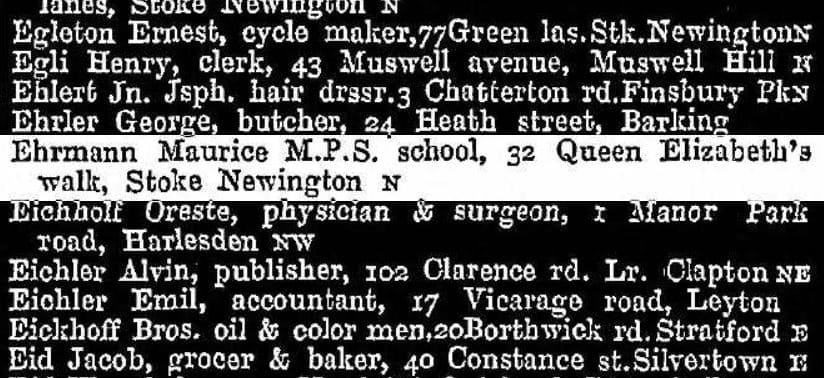

In my original article about the wall, I finished with some mysterious lettering that used to be found at street level. As a result of the discussions about the Pinterest sign on Twitter, Claudia proposed ‘Clissold College’ as a possibility for the top line. I then suggested the second line could have been an address, to which Nick replied with the nearby Queen Elizabeth’s Walk, which would also fit.

Some early searches have revealed that a Maurice Ehrmann, born c1960 in Austria, was operating a school at 32 Queen Elizabeth’s Walk from at least 1894 to 1906. This building number fits with what’s visible on the old sign, and so it seems a likely connection, perhaps with the trading name of the school being Clissold College.

Answers on a postcard…