30 Nov 2020

Restoration Period: My Monotype Recorder Article Now Available to Read Online

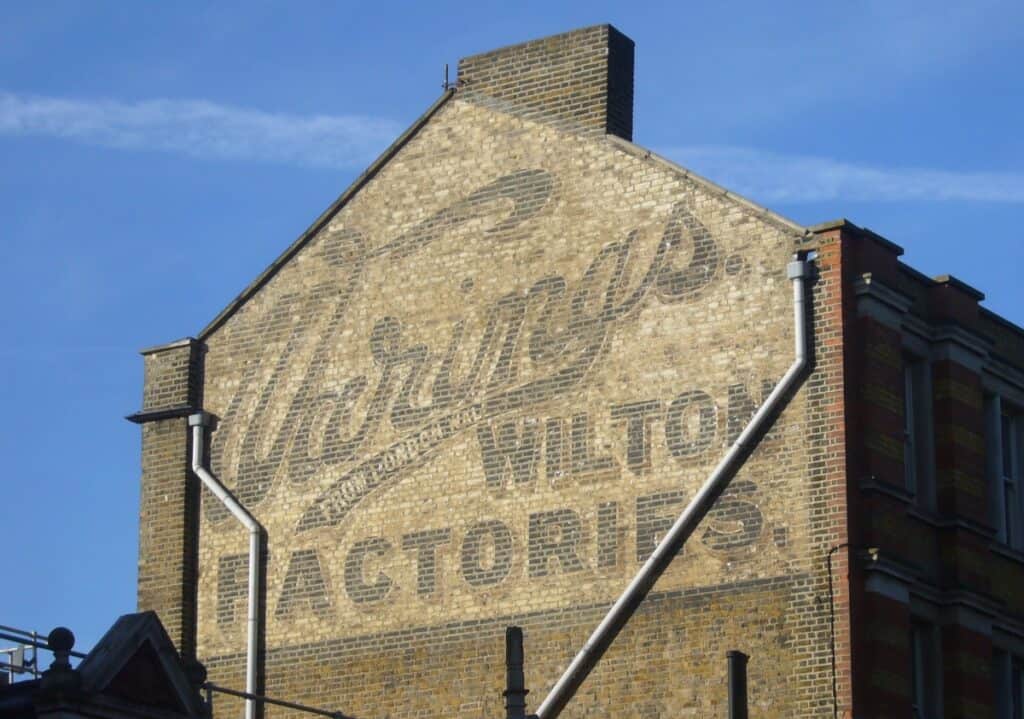

While carrying out some research into London’s ghost signs for a ‘little’ project I’m working on, I discovered that my 2014 piece for the Monotype Recorder (Issue 1) has been made available online.

The article is an extended examination of one of the hottest topics on ghost signs, namely what, if anything, should be done in terms of protection, conservation and restoration. I’ve pasted the text below in full, and the link will take you through to the pretty one with pictures.

Reading through it again, I largely still agree with everything, except for the comments about restoratoin work in the Netherlands which isn’t always as diligent as I claim. That said, I’m happy that, for me at least, this piece has stood the test of time.

Restoration Period

In Butte, Montana, a debate currently rages over what to do with the city’s many ‘ghostsigns’: the fading remains of advertising painted on walls. Jim Jarvis and the Historic Preservation Office have proposed having these repainted by the contemporary collective of mural artists and sign painters known as ‘The Walldogs’. However, local opposition has surfaced, objecting to what is perceived as the ‘Disneyfication’ of the town and a lack of public consultation.

This debate is not unique to Butte, which is just one example of attempts around the world to resolve the question of what, if anything, should be done about ghostsigns. The repainting of a sign for Bile Beans in York, England, provoked reactions both extreme (‘an act of public vandalism’) and acerbic (‘like an old friend having bad plastic surgery’), in addition to widespread praise for the job done. In the absence of any comprehensive and authoritative guidance in this relatively new area of historical interest, the decisions taken are typically at a local level. Community groups and property owners adopt approaches that they believe are right, often gaining support and inciting opposition in equal measure.

As the evidence from Butte and York shows, these signs exist at an intersection of public and private interests. They are typically ‘hosted’ on the walls of private properties, and subject to the whim of building owners. However, the reactions to proposed or actual changes to their appearance demonstrate a parallel sense of public ownership. The signs serve as way markers – often perceived as ‘public art’ – and are records of local advertising and craft history. Conflict between these different groups, with their respective claims to ownership, is brought about when decisions are taken that affect the signs.

These contentious interventions vary in degrees of extremity, from doing nothing, through to plans to repaint the signs en masse as in Butte. Some actions lead to the loss of ghostsigns; the demolition of buildings, whitewashing and sandblasting of walls are all more final than the gradual weathering that usually takes them away. A whitewashing in Clapham led to a question being asked of London’s Mayor about what he was doing to protect these pieces of cultural and commercial history. His response delegated responsibility to local council level and, in this case, Michael Copeman, on behalf of Kate Hoey MP, responded that:

“The character of things like this is essentially ephemeral, and it is the fact that such things survive only rarely and accidentally that gives them their charm and fascination. Although their loss may be regretted, perhaps it is necessary to allow such changes to happen, untouched by a regulatory framework, so that in another hundred years’ time, people may be able to look at different but equally curious survivals – of early 21st century ephemera.”

There is much to commend in this response, although the longevity of today’s billboards and digital displays is clearly inferior to that of the ghostsigns that have survived. Further, it is interesting that the value placed upon the signwriting craft is in some way less than crafts which create more permanent artefacts such as furniture, jewellery and books. Many of these signs are antiques, yet the skills involved in producing them aren’t celebrated in the same way as those of jewellers, cabinet makers and book binders.

Their commercial intent is the main point of difference between ghostsigns and these other crafts, making the motivations of those passionate about them even more intriguing. There isn’t a comparable lobby arguing for the protection and restoration of contemporary billboards, yet ghostsigns once served exactly the same advertising purpose. In 1960 Howard Gossage observed that billboards exist ‘for the sole and express purpose of trespassing on your field of vision’, representing widespread resentment of overbearing outdoor advertising. Further back, in 1855, the ‘One Who Thinks Aloud’ lamented the form, although on very different grounds, ‘Amid all the changes which this changing age has produced, that of the walls superceding the town’s bell-man is perhaps the most melancholy.’

The age of ghostsigns (most are from the early 20th century) triggers a similar nostalgia which, in turn, leads people to cherish them. However, in their day, they provoked opposition similar to that of Gossage and the One Who Thinks Aloud. Although they are often resented now, it is entirely conceivable that the revealing of a printed billboard in 50 years could provoke a similarly nostalgic response, and calls for protection, in a future world dominated by digital advertising.

The point at which ghostsigns assume value is subjective and, currently, a matter of debate. By contrast, most would agree with the preservation of the 2,000-year-old remains of painted advertising in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Likewise, the painted caves of the Ardèche in France, and the rock art of Australia. While not explicitly advertising, they also served some communicative purpose and hold obvious value as cultural relics. Ghostsigns are one among many examples of humankind’s desire to leave a mark, whether for commercial, community or individual ends. The age at which they assume the same value as these older inscriptions is arbitrary and disputed.

Given their ambiguous value, ghostsigns currently fall outside of approaches taken to preserving cultural heritage artefacts. They are not architectural features of note and are, ultimately, just advertising ephemera. In addition, unlike other forms of advertising and printed matter, they cannot be collected and displayed in archives and museums, at least not in their original form. Photographic archiving projects, such as the UK-based History of Advertising Trust Ghostsigns Archive, do catalogue and document material, but say nothing about how ghostsigns ‘in the wild’ should be treated. Attempts to develop systematic approaches to protection and restoration all face the problem of defining which signs have merit: one person’s artwork is another’s eyesore. Further, ghostsigns often exhibit multiple layers of text, known as ‘palimpsests’, with some seeing a beautiful historical ‘onion’ , while others perceive nothing more than a mess.

The signs often fall victim to today’s graffiti and street artists, getting whitewashed in efforts to ‘clean up’ this more contemporary work. In some instances this coverage is only partial. In Stamford Hill, London, advertising for a cigarette brand is still visible above a painted strip covering graffiti. There is a tension given that tobacco advertising (albeit for a defunct brand) is now just as illegal as graffiti in the UK. The lack of formal guidance for protecting and restoring ghostsigns results in something akin to the Wild West i.e. anything goes provided you have the resources to do it.

Protection, legal or otherwise, is an obvious starting point for those who value ghostsigns. The city of Bath, in England, has inadvertently protected many of its well-preserved signs. This is due to strict planning regulations that apply to their English Heritage listed ‘host’ buildings. A similar situation is found in conservation areas like London’s Stoke Newington and the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham. Two signs in Hackney, London, have recently been given more explicit protection. They have ‘local listed’ status in recognition of their ‘aesthetic or artistic merit’. This stipulates that the signs must ‘be considered’ in planning applications affecting them but this protection is relatively limited in legal terms. Efforts to protect ghostsigns are necessarily piecemeal and constrained by the need to develop an agreed means of assessing the worth of individual signs.

Conservation and restoration present additional options for managing ghostsigns. Conservation is quite rare but a well-known example exists in Fort Collins. In 2011 Deborah Uhl and Lisa Capano ‘rehabilitated’ a 1958 Coca-Cola sign, bringing it back to a legible state, while keeping its faded essence. This approach shows sensitivity but requires judgements about which parts are touched up, or not. These considerations are not particular to ghostsigns; conservation in the art world is a highly contentious issue. The ‘restoration’ of the Sistine Chapel in the 1990s led James Beck to conclude that ‘the authentic masterpiece of Michelangelo…is now severely damaged’. Treatments that affect the natural decay of ghostsigns can be subject to similar assessments of authenticity to avoid such ‘damage’.

Many consider the widespread, and increasing, repainting of ghostsigns as hugely damaging. This was done routinely when they were ‘in service’ to ensure they remained bright and eye-catching. However, there is a superficiality in re applying the paint when they are devoid of their intended advertising purpose. (An exception is the many Coca-Cola restorations funded by the company itself.) For many, the appeal of ghostsigns is their faded appearance and this is lost when they are repainted. The connection with the past is mediated through the surviving paintwork and this is diminished to some extent with its reapplication years afterwards. While repainting projects do demonstrate what impact the signs would once have had, this could also be achieved by creating new signs, and allowing the craft skills to flourish and develop in new ways.

For the foreseeable future these repainting projects will continue outside of any regulatory framework. Lessons can be learned from the Netherlands where repainting work is carried out in a disciplined and considered manner. Under the guidance of the umbrella group, Tekens Aan de Wand (Writing on the Wall), projects are completed through the use of thorough archival research and professional signwriters with knowledge of traditional methods. This approach is also found elsewhere but there are plenty of examples where little or no thought has been given to undertaking the work in an authentic and considerate manner.

The debate about what should be done with ghostsigns will not go away. Indeed, it is important to nurture it so that opposing views can be subjected to scrutiny and discussed among those with an interest in these pieces of painted history. Study of cases such as those highlighted in this article can contribute to this debate, and allow those initiating future projects to learn from what has been done before. However, for now, the realm of ghostsigns protection and restoration remains a free for all, but beware the backlash if your project fails to consult with those whose field of vision it trespasses on.

Citation: Roberts, S. (2014) Restoration Period, The Recorder, Issue 1, Monotype

Thank you to Monotype for permission to reprint the text of this article here.