22 Jun 2018

The Grand Exhibition of the Society of Sign Painters

The following article is re-posted from the original on Better Letters.

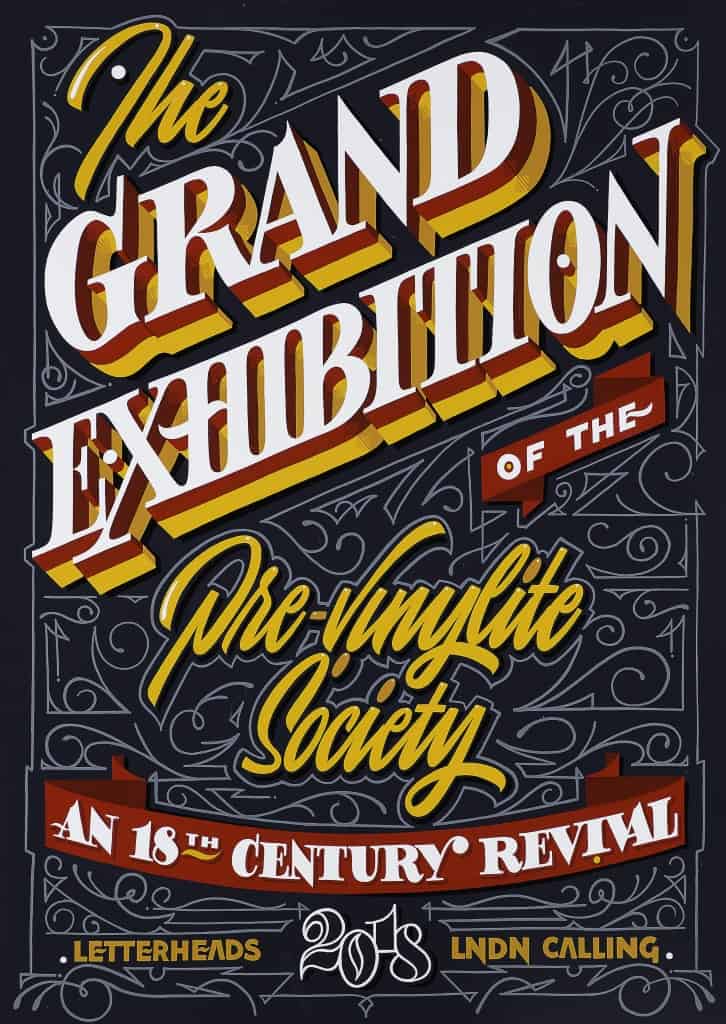

This August we’ll be opening a very special sign painting exhibition within the public-facing part of Letterheads 2018: London Calling. It is being curated by Meredith Kasabian of Best Dressed Signs and the Pre-Vinylite Society and builds on her research into an 18th Century exhibition that happened a short distance away in Covent Garden. We’ve invited Meredith to share some of her research in this guest post to whet the appetite for the forthcoming contemporary interpretation of this historic event…

The 1762 Grand Exhibition of the Society of Sign Painters: A Burlesque of the Times

By Meredith Kasabian

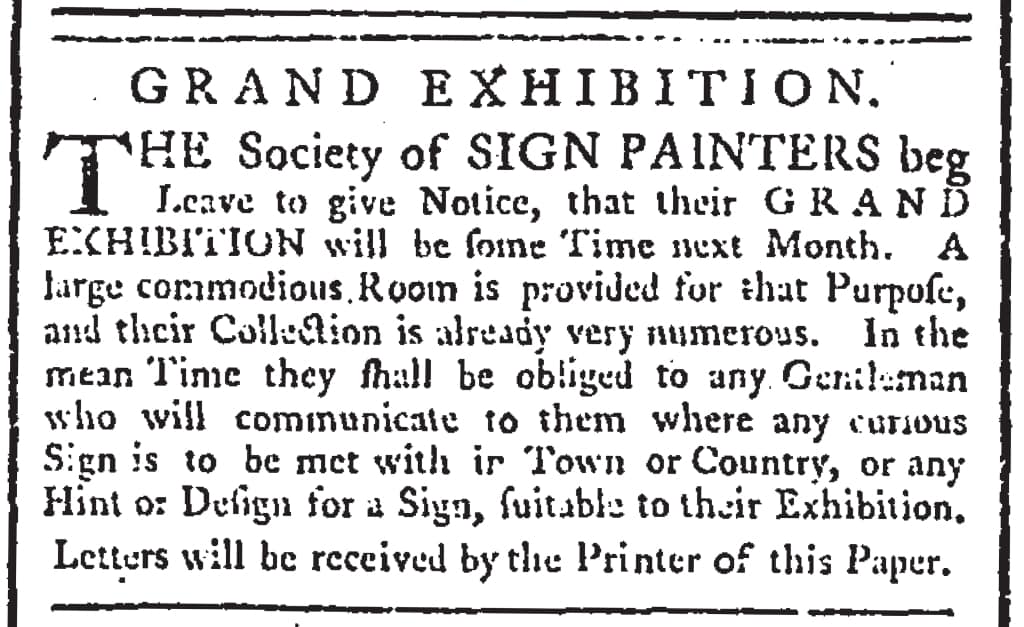

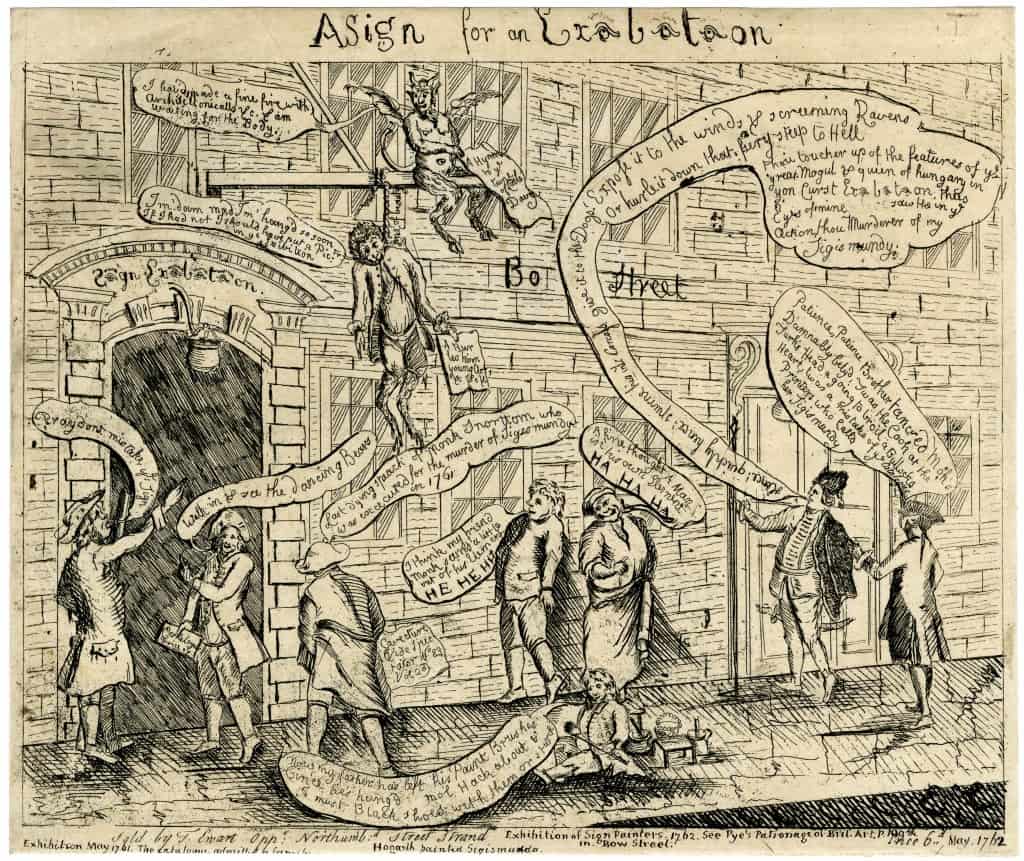

In the spring of 1762, scores of curious Londoners paid one shilling per admission for the chance to glimpse the new exhibition by London’s fictional Society of Sign Painters. This “Grand Exhibition” (Fig. 1, above) presented the nation with a satirical display of pictorial signboards, some painted specifically for the show (purportedly by William Hogarth, whose streetscape paintings and engravings often featured London’s signs (Figs. 2 and 3, below)) and some taken clandestinely from the city streets in the aftermath of a sign ordinance, which required all projecting signs to be removed. The enactment of this city ordinance—along with a desire to mock the concurrent exhibition at the Society of Arts—prompted journalist Bonnell Thornton and his fellow London wits, known as the Nonsense Club, to seek out, take down, and display these pictorial signboards in the world’s first gallery exhibition of hand-painted signs.

The 1762 Grand Exhibition of the Society of Sign Painters was staged in response to a pervasive culture of connoisseurship, which favored art and artists from the European continent over native-born British artists. While the Society of Arts claimed to champion British artists, their focus on royal patronage clashed with the ideals of Thornton, Hogarth (a former member of the Society of Arts), and the Nonsense Club. This prompted them to schedule their Society of Sign Painters’ mock exhibition to in proximity to, and concurrently with, the exhibition at the Society of Arts. By placing the “low” art of sign painting in a gallery setting near the exhibition at the Society of Arts, the Society of Sign Painters effectively burlesqued the novel practice of the public art exhibition. Simultaneously the also managed to lampoon the signs, the sign painters who made them, and the public, who were duped into believing the Society of Sign Painters’ exhibition was an earnest endeavor to further the cause of native British artists.

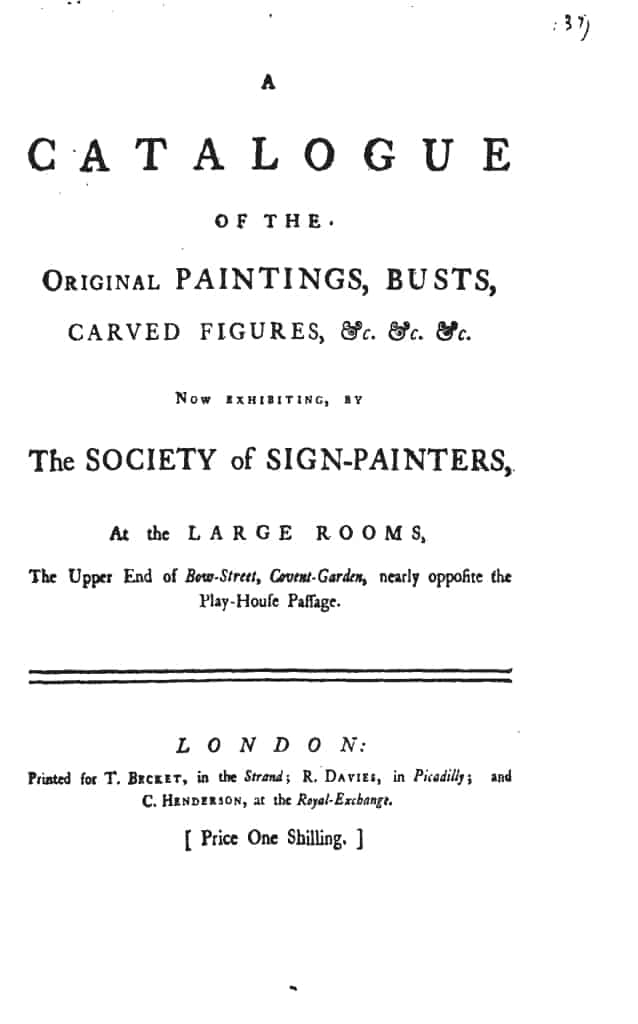

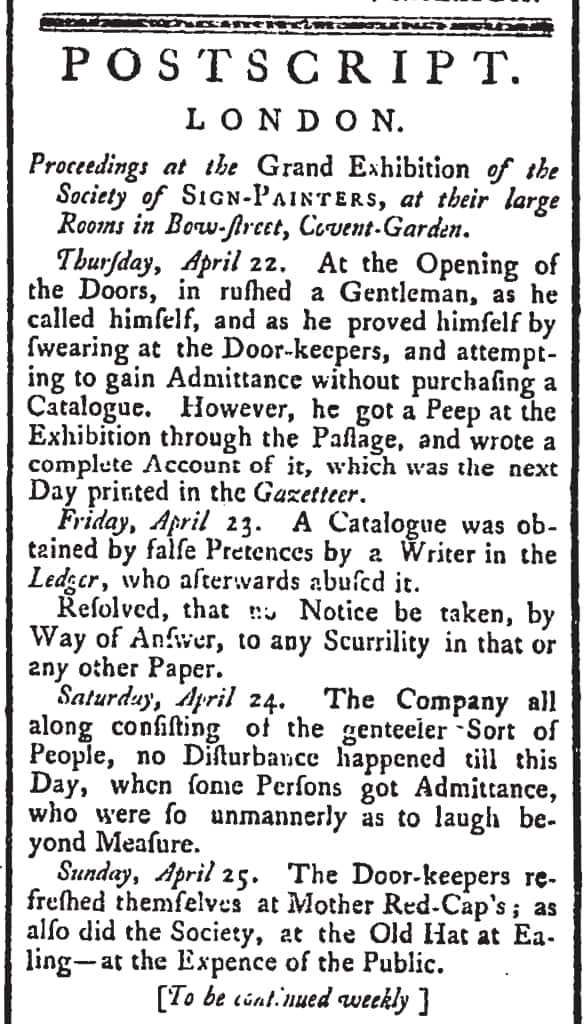

The Society of Sign Painters printed a companion catalogue that described the signs on view and served as a ticket to the exhibition at a cost of one shilling per admission (Fig. 4, above). The catalogue included a detachable page, which was ripped off when entering the exhibition so that a patron could not see the exhibition twice without purchasing another catalogue. In an account of the event printed in the St. James’s Chronicle—a tri-weekly newspaper owned in part by Thornton and other Nonsense Club members—the organizers explain that on April 25th, three days after the exhibition’s opening, “the Door-keepers refreshed themselves at Mother Red-Cap’s; as also did the Society, at the Old Hat in Ealing—at the Expence of the Public” (Fig. 5, below). While the admission price for the Society of Arts’ exhibition supplemented the artists and the mission to inspire a more positive perception of British art, the admission price at the Society of Sign Painters’ exhibition funded a night out for drinks at the pub.

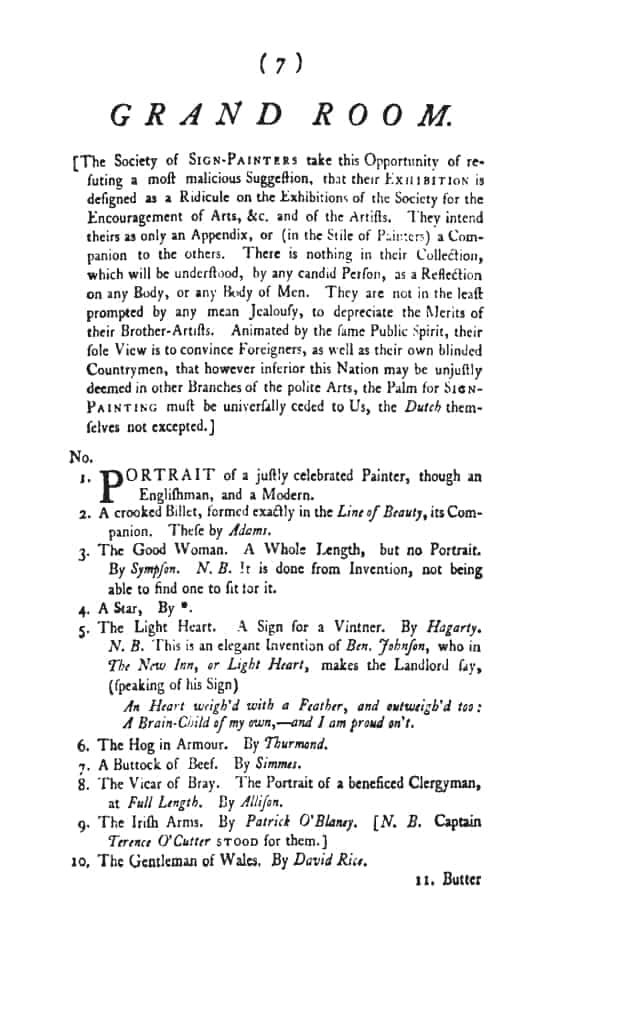

While the Society of Sign Painters maintained that the Grand Exhibition be taken seriously as a celebration of the skill of England’s sign makers (Fig. 6, below), the witty tone of the exhibition cannot be overlooked. As Jonathan Conlin, author of “‘At the Expense of the Public’: The Sign Painters’ Exhibition of 1762 and the Public Sphere,” points out, “to take [Thornton] at his word requires making several assumptions that would have been impossible for many contemporaries to accept—first, that British signs were in fact something to celebrate and, more importantly, that signs were ‘art’ and could be discussed by an attentive public in aesthetic terms” (p.2). Art historian James Ayres agrees that to take the Society of Sign Painters at their word requires an anachronistic suggestion that they were engaging in a commentary on the nature of art itself. He proposes that “an important clue to the intention behind this exhibition was a quote from Horace’s Ars Poetica prominently rendered in the gallery in gold letters on a blue ground: SPECTATUM ADMISSI RISUM TENEATIS (You who are let in look restrain your laughter)” (p.313).

This laughter, however, was apparently not intended to be stifled. The proliferation of printed matter surrounding the Grand Exhibition included many humorous descriptions, reviews, objections, and even satirical cartoons that lampooned the exhibition and its organizers (Fig. 7, below). In one of several reviews of the exhibition, an anonymous contributor to the publication, ‘Dialogues of the Living’, describes the exhibition, including the “joke” that on either side of the chimney, “are two curtains hanging down, which you would suppose hid something very curious, but on lifting them up you see behind one Ha! Ha! Ha! and the other He! He! He!” (p.92). These “signs,” concealed by a velvet curtain (often employed in this era to censor sexually provocative content) correspond to numbers 49 and 50 in the Society of Sign Painters’ catalogue, which are described as:

“These two by an unknown Hand, the Exhibitors being favoured with them from an unknown Quarter. ***Ladies and Gentlemen are requested not to finger them, as Blue Curtains are hung over on purpose to preserve them” (p.9).

By compelling an interaction between the viewer and the artwork, the blue curtains served as a tangible way for the Society of Sign Painters to bring the audience in on the joke and assert the exhibition’s intention as a mockery of the novel phenomenon of the public art exhibition, specifically the concurrent exhibition at the Society of Arts.

Many things have changed in the 256 years since the men behind the Society of Sign Painters’ exhibition used the medium of signage to express their varied views on 18th century London life, including the assertion that signs should not be considered art. As a response to this historic event, the Pre-Vinylite Society presents our own exhibition of hand-painted signs, to be exhibited this August at the 2018 Letterheads event in London.

The Grand Exhibition of the Pre-Vinylite Society: An 18th Century Revival (Fig. 8, below) is a contemporary interpretation of the Society of Sign Painters’ exhibition that celebrates our current 21st century sign painting renaissance as a gallery-worthy enterprise. Our Grand Exhibition of the Pre-Vinylite Society features a global assembly of sign painters working directly from the 1762 catalogue to translate the historic descriptions into contemporary lettering and pictorial styles. While the original exhibition aimed to burlesque the Society of Arts’ mission to encourage native British artists, the Pre-Vinylite Society’s exhibition champions the global resurgence of sign painting while advocating for more diversity in our field.

More information on the original Society of Sign Painters’ exhibition and 18th century signs in general will be available in the Grand Exhibition of the Pre-Vinylite Society’s companion catalogue, available for purchase at the gallery at Bargehouse, Oxo Tower Wharf, August 16-19, 2018.

Works Cited

- Ayres, James. “The Vernacular Art of the Artisan in England.” The Magazines Antiques. 151.2 (1997): 312-321.

- Conlin, Jonathan. “’At the Expense of the Public’”: The Sign Painters’ Exhibition of 1762 and the Public Sphere.” Eighteenth Century Studies. 36.1 (2002): 1-21. Dialogues of the Living. Printed for J. Cooke, at Shakespeare’s-Head, in Pater-Noster-Row, 1762. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

- Society of Sign-painters. A catalogue of the original paintings, busts, carved figures, &c. &c. &c. now exhibiting, by the Society of Sign-Painters, at the large rooms, the upper end of Bow-Street, Covent-Garden, nearly opposite the play-house passage. London, 1762. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

- St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post (London, England), April 27, 1762 -April 29, 1762; Issue 177.