18 Jan 2021

The Enduring Mystery of the Peterkin Custard Ghost Sign

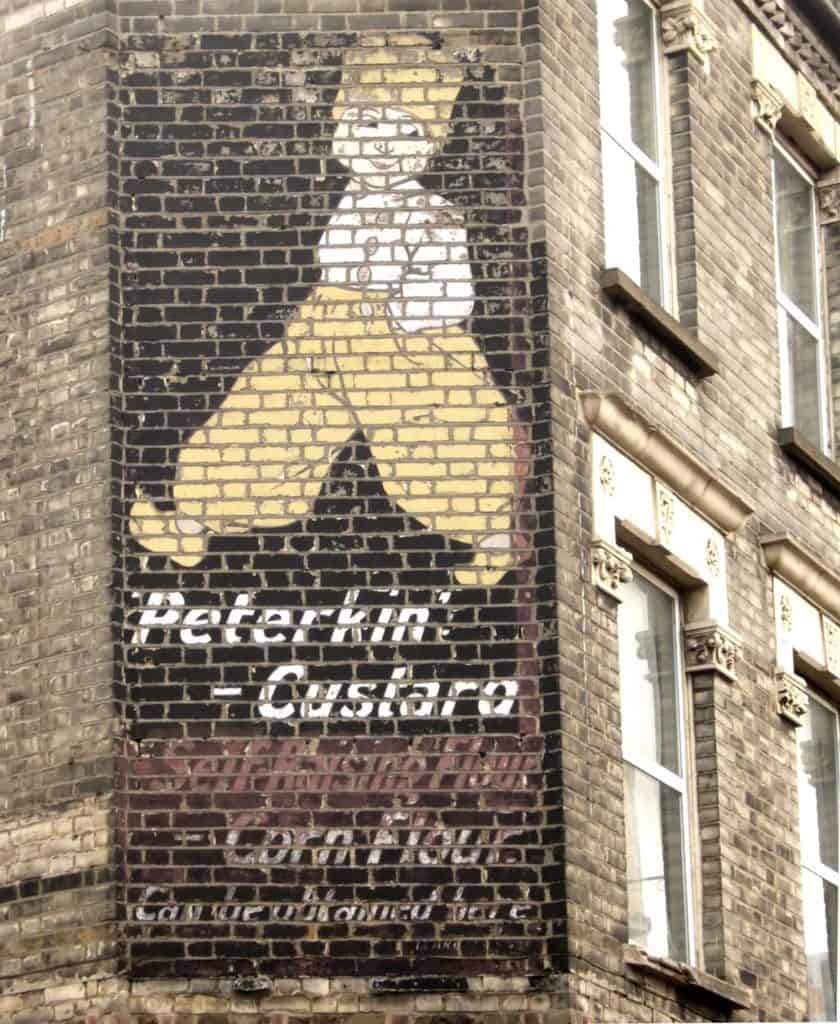

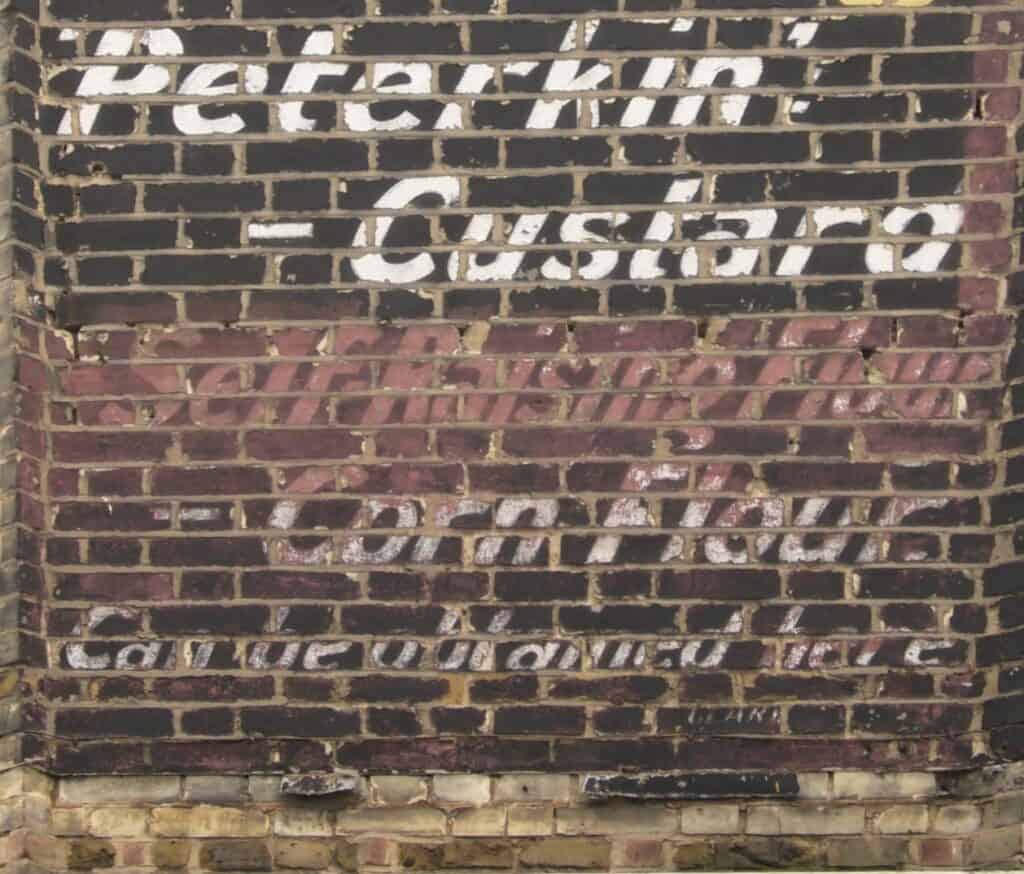

The enduring mystery of the Peterkin Custard ghost sign in Battersea continues but, since I posted about it in 2007, further information has come to light. Here I’ll share what I’ve found out in the hope that someone in the future might be able to finally unlock the secrets hidden behind this iconic London ghost sign.

The Peterkin Story (So Far)

The Peterkin brand appears to have been something of a flash-in-the-pan affair during the 1920s and a little either side of that decade. Its origins are unknown, with the first record of their existence being the purchase of Peterkin Self-Raising flour by baking magnate Joseph Rank.Despite considering him to be a ‘dunce’ Rank Senior bought Peterkin for his son, Joseph Arthur Rank, shortly after the end of the first world war, so c.1919. (Sebastien Ardouin states that it was a product launched within the Rank business, which would explain the lack of references prior to the 1920s.)

Rank Junior couldn’t make a success of it and sold up. Although he then spent some time working for his father’s firm, he would later strike out alone and enjoyed great success with the Rank film empire that he created.

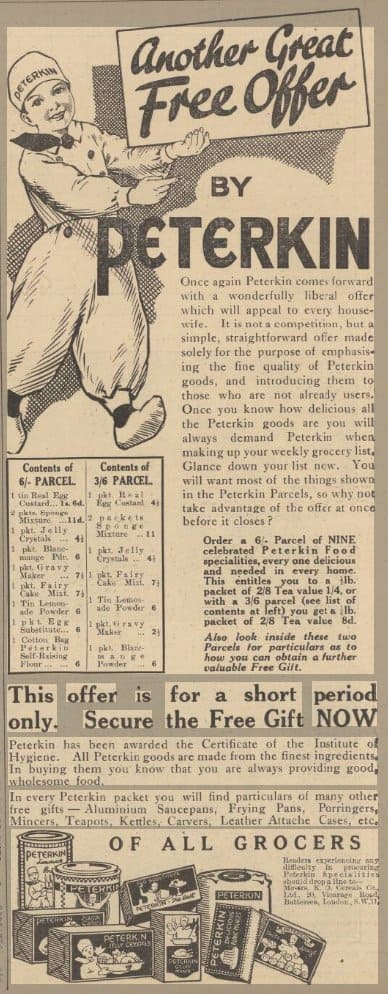

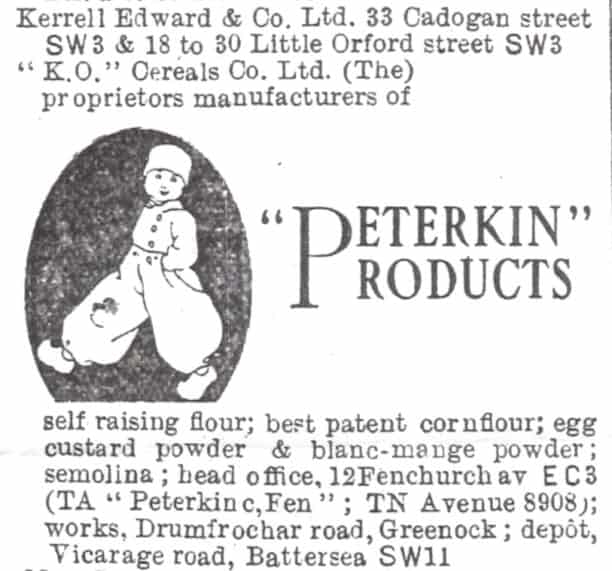

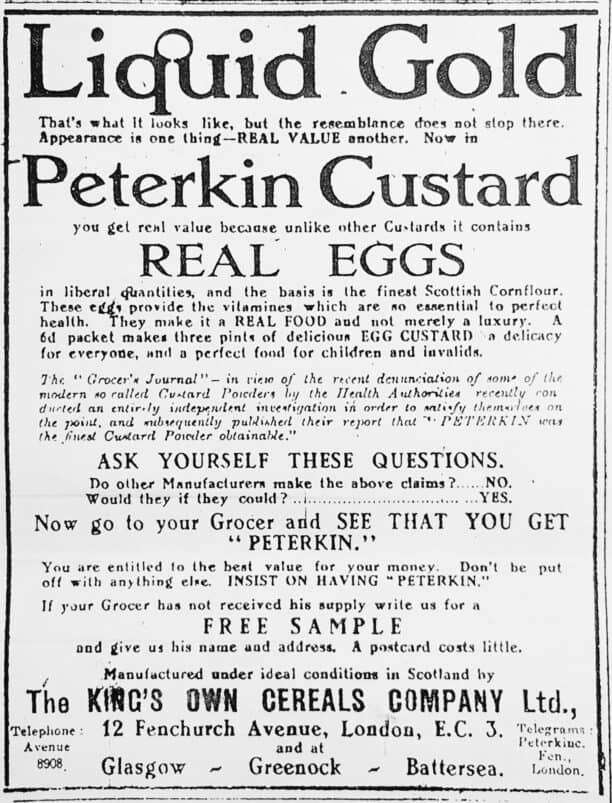

The buyers of the brand from Rank look to have been The King’s Own Cereal Company Ltd, a Scottish firm with London offices in Fenchurch Avenue and mills in Battersea, not far from this sign. They are listed on a 1921 advertisement which would make Rank Junior’s tenure very short indeed, two years at most.

In 1922 a trade directory advertisement has the brand listed under Edward Kerrell & Co. Ltd. There is still a reference to The “K.O.” (King’s Own) Cereal Company Ltd, and this is the only name given on a 1926 advertisement. This suggests that ‘King’s Own’ was by then a trading name within the Edward Kerrell stable.References to Peterkin as a going concern cease from 1930 onwards, but it’s the brand’s origins in the period prior to 1919 that remains something of a mystery.

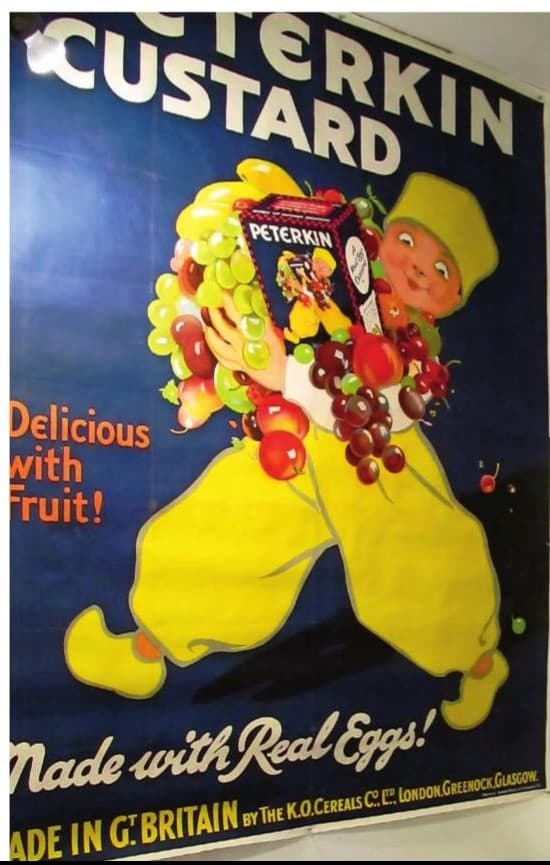

The Dutch Boy

The pictorial has led to this sign’s status as something of a London favourite, including my own enthusiasm for it. Given the uncertainty about the origins of the brand, it is likely that we’ll never know why the name, and this mascot, were chosen.

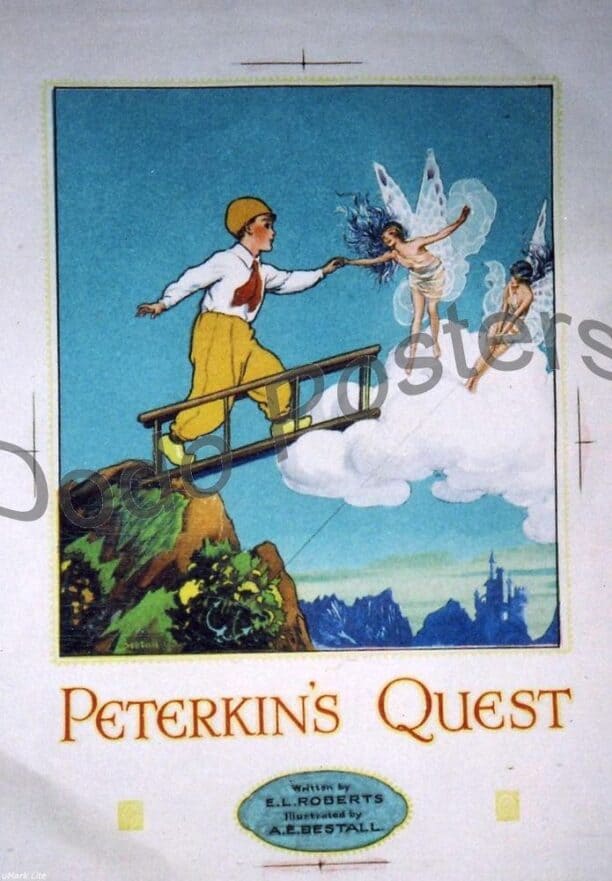

It is possible that the inspiration for the Dutch boy comes from Peterkin characters in stories. (The ‘kin’ suffix means little, and so Peterkin is ‘little Peter.’) These include The Adventures of Peter Peterkin and Peterkin’s Quest which each feature similar illustrations. As @libbyrinth notes on Twitter:

“Peterkin was used by several authors, most notably Howard Pyle in The Wonder Clock’s Peterkin and the Hare*. (Lucretia Hale’s Peterkin Papers are tangential to the main branch.) Not sure whether he is originally from the Netherlands or whether he is a Victorian invention.”

*Peterkin and the Little Grey Hare

While it would be a nice aside, there doesn’t appear to be any connection between this painted sign and the Dutch Boy brand of paints in America. Both do share visual similarities in their iconography and so further understanding the origins of this would be nice to know. However, this knowledge wouldn’t have a huge bearing on the central mystery of this sign, namely its location.

The Sign’s Location

The sign is on 115 St John’s Hill, London SW11, at the corner with Sangora Road. It is positioned on the chamfer of the building, above the entrance to the shop. This positioning is often used for signage, providing good visibility from different angles of approach versus a wall that is perpendicular to the main street.

The obvious conclusion is that this is a privilege, paid for by Peterkin, but situated on the site of a retailer where the product is available, as with the many Hovis signs across the Capital. Given the connections between Hovis and the Rank empire it wouldn’t be surprising to see the strategy adopted for Peterkin by Rank Junior. The name and trade of a retailer would have fitted nicely in the top portion of the wall above the boy’s head (see Streetview) and could have been lost while the area below was protected by a later mounted sign board.

However, the records of businesses in the building don’t support the privilege theory. In fact, for some time before and after the period under consideration, the premises were consistently occupied by one family firm. They were the Cato family and their trade was oil and colour men, essentially selling paints, and they can be placed in the shop for at least 1891–1941.

Nonetheless, the sign itself clearly states “can be obtained here” with reference to the Peterkin products listed. I cannot reconcile these two facts as it seem inconceivable that a paint seller would have a significant sideline in powdered cooking goods. This is at the heart of the mystery behind this beautiful sign and I would welcome any leads or information that can help to square the circle.

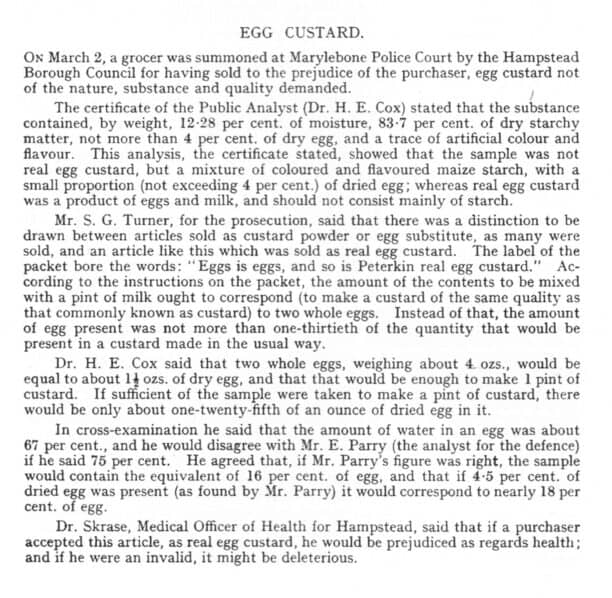

Eggs is Eggs. Or Are They?

One thing that is clear is the promotion of Peterkin’s custard powder with reference to the “real eggs” that it contained. The copy on their 1921 ‘Liquid Gold’ advertisement asks rhetorically “Do other manufacturers make these claims?” before responding with a firm “no”, immediately followed by “Would they if they could?” and an emphatic “yes.”

This confidence was somewhat misguided. In 1926 a grocer was hauled up before the court for selling packets of Peterkin custard powder which contained only minimal egg content. The labels of these stated that “Eggs is eggs, and so is Peterkin real egg custard.” In concluding an article on the matter in trade publication Analyst Journal it was noted that:

“Dr. Skrase, Medical Office for Health for Hampstead, said that if the purchaser accepted this article, as real egg custard, he would be prejudiced as regards health; and if he were an invalid, it might be deleterious.”

However, the case was dismissed given the lack of applicable standards for custard powder. And that the very low price of the product should have served as hint to customers that it wasn’t all it was ‘cracked’ up to be.

It would be neat if this was the start of the brand’s downfall in the later years of the 1920s. However, what lives on is this mysterious ghost sign, a sprinkling of contemporary print advertising, and speculation regarding some of the questions they collectively raise. Answers on a postcard, or by email or the comments below.

Thank you to Nicola Hale and those that responded to my tweet about the sign.